History of Beauvale Priory

Beauvale Priory was founded in 1343 by Nicholas de Cantilupe, one of nine priories to be built in England dedicated to the Carthusian Order of monks. The monks lived a silent life here at Beauvale for 200 years until the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when they refused to sign the Oath of Supremacy acknowledging Henry VIII as the head of the Church. Through English Heritage, a specialist team of conservation architects and archaeologists have been working to preserve and consolidate the priory ruins and the gatehouse.

Only nine of their charterhouses ever flourished in this country. The community survived peacefully living a life of worship and work for nearly two centuries until the disruption of the Reformation. Beauvale was distinguished by two of its priors, St. John Houghton and St. Robert Lawrence, who became the Pro-martyrs (the first), of the Reformation and were canonized, (declared Saints) in 1970.

Story of Beauvale Priory and the Martyrs

By M. Roberts, excerpts from the above book below, available for sale in the tearoom.

Beauvale Priory was founded in 1343 by Sir Nicholas de Cantilupe. The monks at Beauvale were Carthusians. Only nine of their charterhouses ever flourished in this country. The community survived peacefully living a life of worship and work for nearly two centuries until the disruption of the Reformation. Beauvale was distinguished by two of its priors, St. John Houghton and St. Robert Lawrence, who became the Pro-martyrs (the first), of the Reformation and were canonised, (declared Saints) in 1970.

Visit our Tearoom and visit the Priory

The Site and Buildings

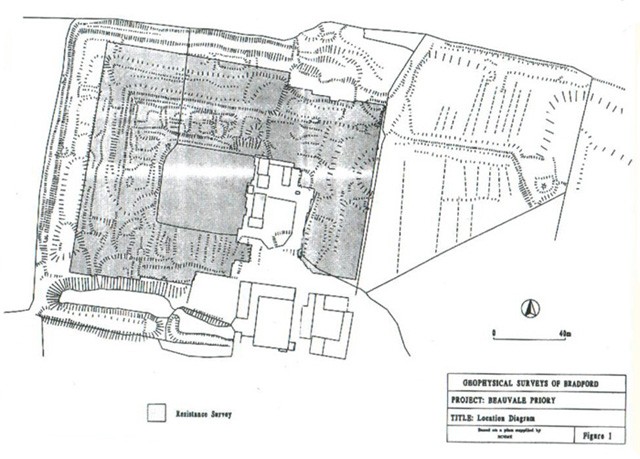

In preparation for building the charterhouse, the ground was levelled to form a rectangular platform. The area covered by the site measures 470 feet from east to west by 290 feet from north to south.

Sir Nicholas had promised to erect temporary accommodation for the first arrivals. He had also promised to build, ‘a fit church and houses’.

The first temporary houses or cells would most probably have been of wood. The monks had permission to quarry for stone. The easily gained local stone is calcareous sandstone mainly of a deep apricot colour shading to deeper red-brown. It is not a stone that weathers well. A superior Derbyshire grit stone was used for dressing to windows, pillars and doorways.Parts of the interior walls still have remnants of plaster which presupposes that all, or most of, the walls would have been plastered. Possibly the exterior walls were plastered too.

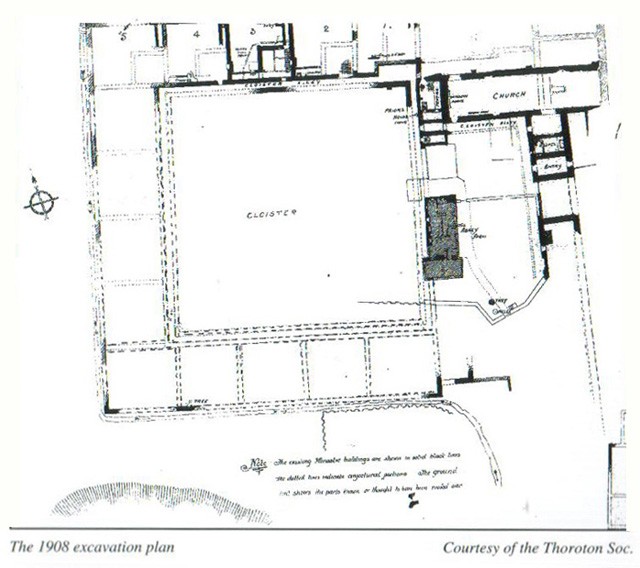

The Church

This was the main and the most important building. It is thought that, being central to Carthusian life, it would have been built in the first phase of work and be of stone. The church was altered and extended to the east or altar end, within a short time of the first build. Larger windows were installed at the same time. The south wall of the church still stands, with the remains of one of the windows. What little remains of the north wall is in a very precarious state. The high altar was where the Beauvale Society’s stone, commemorating the martyrs, now stands. The founder’s tomb was not used by Sir Nicholas. He was buried in Lincoln Cathedral.

Carthusian churches were small, plain and usually without aisles. A solid screen would have divided the lay brothers from the choir monks. There were no gold or silver vessels or ornaments used except for a silver chalice. Copes and monstrances were unknown in Carthusian churches. Instrumental music was forbidden.

The Chapter-House & Cloisters

The chapter-house at Beauvale has not been excavated but is mentioned in the priory surrender document [after the priory was handed over to the royal commission in July 1539]. Judging from the layout of other Carthusian houses it should be on the north-east side of the church. All the community would meet there, usually on Sundays, to discuss business relating to the priory and deal with any matter of discipline.

The cloister area, now the orchard, can be seen clearly on both plans to be surrounded on the south, north and west sides by the outlines of the cells. Sir Nicholas provided twelve cells and at a later date at least two more were added. The geophysical survey of the orchard also indicates a water-tower with pipes leading off. In the Carthusian tradition the cloister was used as the monks’ burial ground. Carthusians were buried in their robes without a coffin.

The Cells were self contained. The ground floor, according to the Thoroton plan, was divided into three small rooms or areas and and there was almost certainly an upper floor used as a workshop. The rooms were sparsely furnished. A bed with a mattress of ‘chaffe or staw’, a prie-Dieu (prayer bench) and a table, and chair were sufficient for a monk’s needs. Fragments of a chimney were found during the excavation in 1908 so it is most likely that the cells had fireplaces.

An ambulatory or covered passage extended from the cell into the garden space for exercising during poor weather. There was a fresh water supply and latrines in each garden, managed by the clever diversion of a stream which, at Beauvale, flowed from east of the site. Lead piping found indicates that rain water was possibly collected. The walls of the gardens were built so high that there would be no visible contact with neighbouring cells or any other area of the priory.

The Prior’s House

This building is substantial and the best preserved structure of the Beauvale site. It is commonly referred to as the prior’s house. Inside can be seen two fire-places and the void left from where a spiral stair-case has been at one time. Looking at the prior’s house from the cloister there are two arched entrances. If it was the prior’s house he would have a grand-stand view over the cloister. The refectory, of which there is no visible trace, would probably have occupied the east side of the cloister where the farm cottage now stands. Communal meals would be taken here on Sundays and feast days by all the monks.

The Gatehouse and Guest Accommodation

Although the gatehouse (now the tearoom, lower right on image left) is still standing it is hard to visualise how much more imposing the entrance would have been. Recently two sets of gate pillars have been partially exposed making it most likely that it would have had a double or triple arched entrance. It was the main entrance into the priory. There are two rooms flanking the entrance. An original wooden wind brace is still in place in the western room.

The guest quarters probably ran to the west of the gatehouse with a porter’s lodge on the east side. Guests were not encouraged and women not catered for at all.The boundary wall still stands along the eastern boundary, to a height of eight feet in places. The whole site was enclosed by high walls cutting off any contact with the surrounding area. The wall runs northwards from the gatehouse, broken only by a postern gate. There are putlock holes penetrating the wall indicating there probably were further buildings abutting the boundary wall. Evidence from the geophysical plan also suggests that there were possibly buildings beyond the wall.

Daily Life at the Priory 1343 – 1539

The prior and the monks arrived at the site of Beauvale prepared for them by Sir Nicholas, in 1343. For nearly two hundred years the Carthusians led their lives at the priory with little contact with the outside world. Life at Beauvale was far from comfortable and it was a struggle to survive. The Carthusians were appropriately known as ‘Christ’s poor men’. An entry in the ledger or account book demonstrates this poverty. It says that a patron ‘had freely paid to the monks in their necessity in relief of their house’. In the Etwall Charter the priory was said to be in a ‘ruinous’ state and again in a second Etwall Charter in 1370, we read of further help, ‘In aid of their sustentation and of the reparation of their priory, which is said to be ruinous’.

Time doesn’t seem to have improved matters when, in 1413, an extract from the Beauvale Cartulary reads, “they had nothing in treasure, or movable goods wherewith to stock their pasture, pay their debts, or relieve their necessity”.

St. Bruno, the founder of the Carthusian Order, had stipulated that the charterhouses had to be self- supporting and not dependent on funding from others. According to the statutes the monks should not rely on income from masses and chantry chapels. It is evident that the Beauvale community had to break this ideal to survive. The situation was not helped by the death of Sir Nicholas in 1356 only thirteen years after the founding of Beauvale. When, by 1375, his grandsons died without heirs, the Cantilupe patronage came to an end.

Named Priors of Beauvale

William – 1404

Richard de Burton – 1422, 1426

Thomas Metheley – 1468

John Swift – 1478

Thomas Wydder – 1482

Nicholas Warte – 1486

John Houghton – 1531

Robert Lawrence – 1531 to 1535

Thomas Woodcock – 1537 to 1539

A Life of Prayer

The monks spent many hours a day alone in their cells and the remaining time in communal worship in the church. It was a hard life filled with work, sleep and prayer. The monastic routine was arduous, with the monks attending church at 12pm for the office of Matins preceded and followed by Lauds, with private prayer in their cells until 2.30am. At 5.45am Prime was recited in the cells followed by Conventual Mass at 7am.

They returned to their cells for an hour for meditation or manual labour until 10am when Terse was said privately in the cells. The remaining time until noon was spent working or reading. None was said alone in the cells followed by study or work until 2.30pm when the office of Colloquium was recited privately in the cells. Later in the afternoon it was back to the church for Vespers. The office of Compline was recited in the cells before going to bed, to be ready at midnight for the cycle of prayer to begin again.

DH Lawrence at Beauvale

Beauvale is in part of D.H.Lawrence’s “Country of my Heart” and features in a couple of his novels as The Abbey and he writes a short story based here called “A Fragment of Stained Glass”